Why the neobank dream is very much alive in Francophone Africa

Four months ago, I relocated to Dakar, Senegal after joining Partech Africa’s VC team as an analyst. Like any new expat, I decided to open a local bank account. But what was supposed to be a routine procedure turned into a compelling pitch for neobanks in Francophone West Africa.

It took a total of 7 weeks, 5 visits to the branch, several hours in the queue and multiple phone calls just to get a working bank account with a debit card.

Oddly enough, the most consequential thing I did in the intervening 3 weeks while I waited for my debit card (after receiving an account number), was to connect my bank account to the Wave mobile money app. With Wave, I could withdraw cash from my bank account and make cashless payments at several locations in Dakar, effectively erasing the need for a debit card or physical visits to the bank.1

Obviously, my experience is just a single anecdote but the early success of venture-backed neobanks such as Djamo and mobile money platforms such as Wave suggests that the customer experience offered by banks in the region leaves a lot to be desired.2

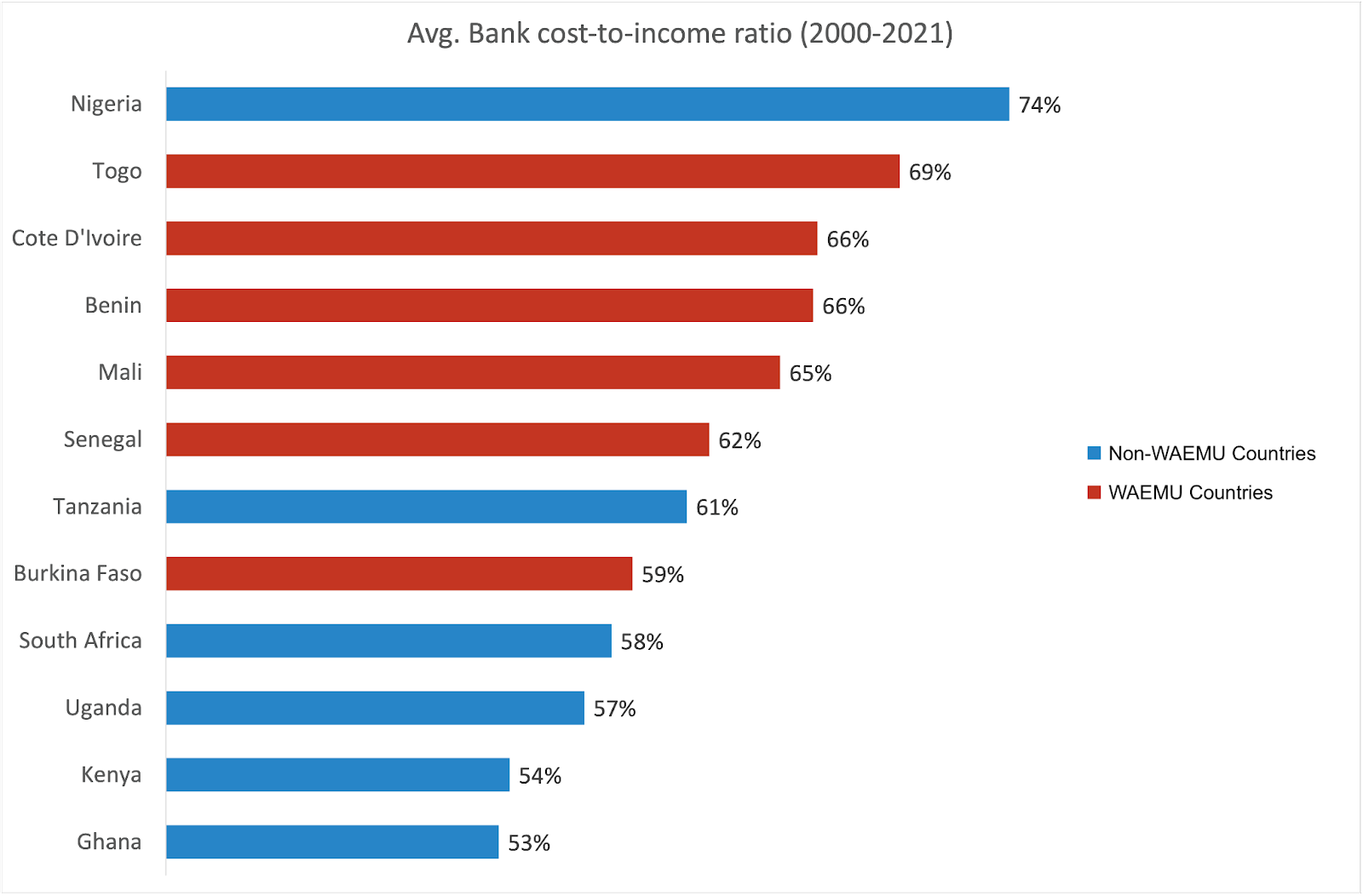

On average, banks in the WAEMU (West African Economic and Monetary Union) have much higher cost-to-income ratios than their counterparts in Anglophone Africa, as shown in the chart below.

Source: The Global Economy

WAEMU banks are bloated with unreasonably high headcount to customer ratios. For instance, as part of the account-opening process, I had to interface with 6 different bank employees, including one who was assigned to me as my ‘personal banker’. Contrast this with Djamo, which allows users in Cote D’Ivoire to digitally open accounts and get debit cards within 2 days.

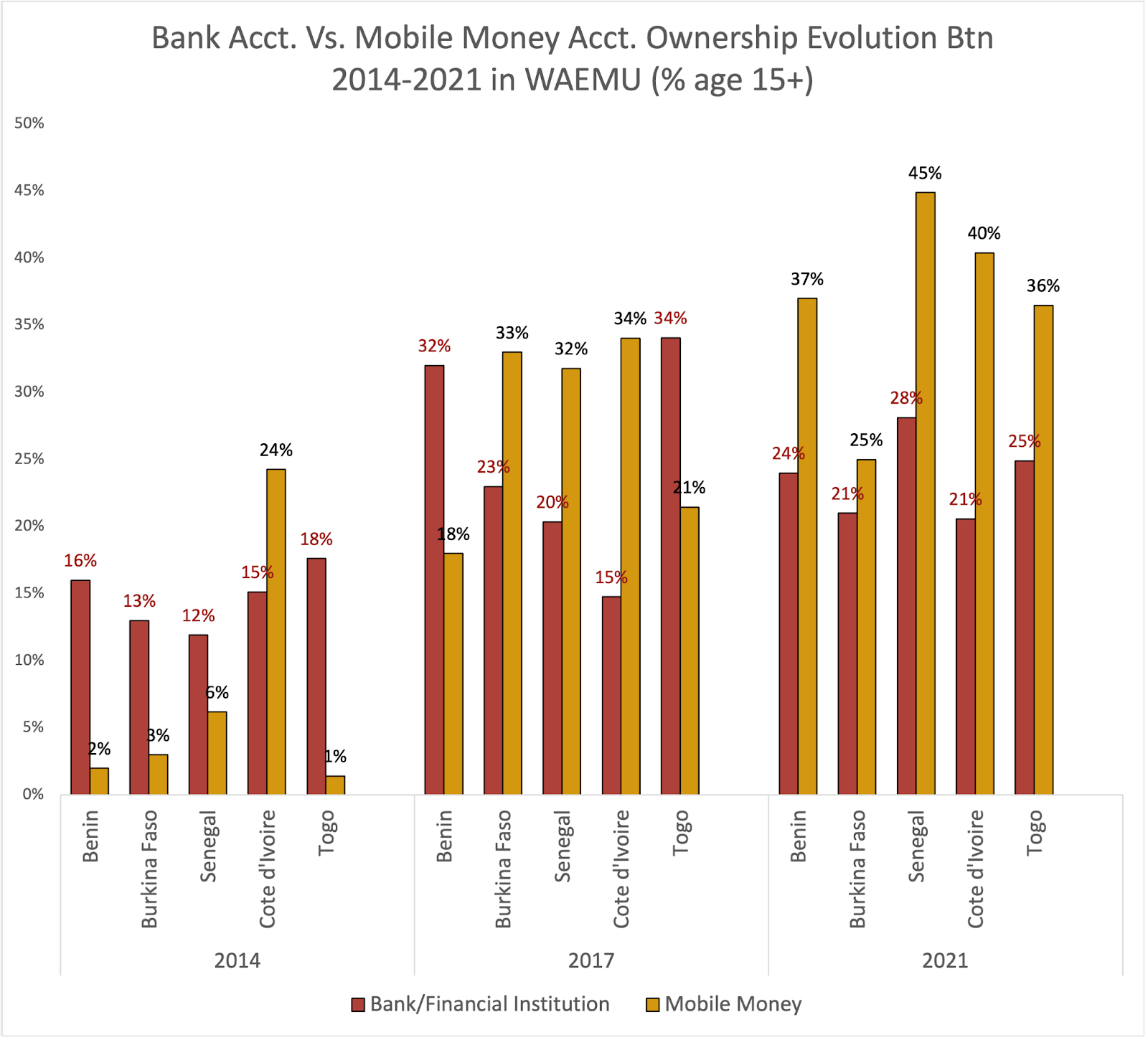

Because of this higher cost-base, banks in the region can only profitably serve a small fraction of the population. Over the last 8 years, mobile money account ownership in the WAEMU region has grown from almost 0% to about 40% of the adult population, while bank account ownership remains between 20–30%, as shown in the chart below.

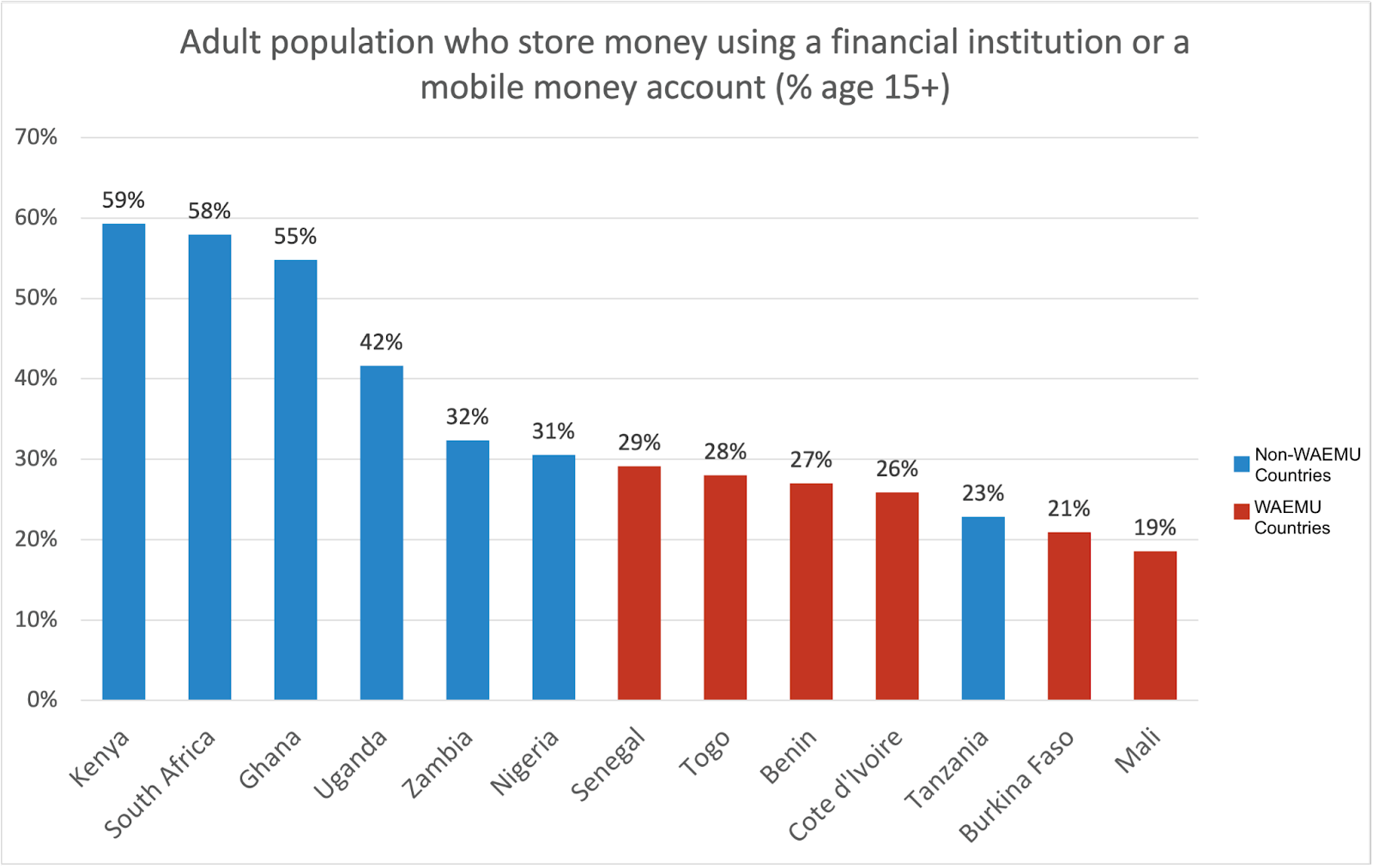

However, despite the meritorious growth of mobile money in the WAEMU region, the rate of adults who store money in either a financial institution or mobile money accounts is still amongst the lowest in sub-saharan Africa, as shown in the chart below.

Source: World Bank Global Findex Database

The rate at which adults in Kenya use mobile money or banks to store their money is 2x higher than in the WAEMU region. And herein lies the opportunity for consumer fintechs in WAEMU. There’s a lot of whitespace to build competitive products as consumers gradually shift their spend away from cash.

Source: World Bank Global Findex Database

It remains to be seen to what extent neobanks can take market share away from the incumbents. Meanwhile, many of the traditional banks are attempting to reduce their costs by adopting agency banking and digital capabilities.

But to the extent that neobanks succeed by focusing on the needs of customers who are currently underserved by the status quo, then those focusing on WAEMU have the highest odds of success.

What’s more, WAEMU is particularly attractive because financial institutions only need one license to scale across all 8 countries in the region, thanks to a monetary union with a single central bank.